POLISH ARMED FORCES IN THE WEST IN 1939-1947

Wojciech Markert

Józef Piłsudski Museum in Sulejówek

ARM IN ARM WITH FRANCE

Polish war plans in 1939 foresaw an armed combat in close concert with the allies: the United Kingdom and France. At the same time, the authorities were also aware that the flare-up of the conflict would require the deployment of all available capacity. As soon as the war broke out, a decision was taken to make use of the lessons learned from years of fighting for independence and set up army units abroad. As early as 9 September 1939, Poland concluded an agreement to create a division composed of Polish volunteers in France.

After the September defeat, despite having to flee the country, the Polish authorities decided to expand the agreement in order to continue fighting at the side of the Allies. On 4 January 1940, the prime minister of the government in exile and commander-in-chief, General Władysław Sikorski, signed an agreement with the French government on the formation of a Polish Army numbering about 85,000 men. While not yet fully operational by the time the Third Reich invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and France on 10 May 1940, Polish troops took part in the French campaign.

However, they were thrown into battle in a dispersed manner, on different sections of the front, and thus could not significantly affect the outcome of the campaign.

After fierce fighting at Lagarde, the 1st Grenadier Division was surrounded and disbanded on 21 June.

The 2nd Rifle Division successfully defended itself on the Clos-du-Doubs hills and, following the retreat of Allied forces, managed to break through to Switzerland, where its soldiers were interned for the rest of the war. The reconstituted 10th Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Stanisław Maczek, was disbanded after a brilliant retreat in Champaign. Split in groups, the men carried out the order to destroy the brigade’s vehicles and found their way to Great Britain.

Formed as part of the Allied expeditionary corps to help Finland repel the Soviet invasion, the Polish Independent Highland Brigade was another unit to distinguish itself. Transferred to Norway, it took part in the battles of Narvik, contributing to the Allied victory there in late May 1940. After the Allied withdrawal from Scandinavia, the brigade was withdrawn to Brittany, where it was soon disbanded. After the fall of France, some of its soldiers were evacuated to Britain together with the remnants of destroyed units and those that had not yet reached corps strength and were not battle ready (this included the 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions). In June 1940, a total of about 25,000 Polish soldiers were transported across the English Channel.

THE ISLAND OF LAST HOPE

After the fall of France, Britain became Europe’s last European bastion of resistance against the Third Reich. It provided refuge to the governments and reconstituted armies of many countries that had fallen to the Nazis, including Poland. While insufficiently armed, the Polish Army units rescued from France were a significant support for England in the critical months of 1940 when the country faced the threat of German invasion. At the time, the Poles were London’s main ally. Concluded on 5 August 1940, the Polish-British agreement on the financing and stay of Polish units in Britain enabled the reorganisation of Polish troops. The Polish I Corps was formed on 28 September on the Commander-in-Chief’s orders and assigned the task of defending the Scottish coast.

Most of the units being formed were only at cadre strength due to a shortage of soldiers. The recruitment campaign disappointed, with the number of volunteers recruited from among the Polish diaspora in America falling short of expectations and needs. The situation improved only when some of the troops evacuated from the Soviet Union by General Władysław Anders had been sent to Scotland and joined the Air Force. However, only the 1st Armoured Division, formed by General Stanisław Maczek, reached full strength. The 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, which was created out of the Polish I Corps in 1941 and subordinated directly to the Commander-in-Chief, was only 70 percent complete when it entered combat in September 1944 despite being prioritised for receiving reinforcements and new recruits.

1943 saw the Polish I Corps being transformed into the Polish I Armoured-Mechanised Corps, a unit which had not, however, been completely formed. Except for the 1st Armoured Division, all other units (including Brigadier General Kazimierz Glabisz’s 4th Infantry Division) did not complete formation and never entered combat. The Polish I Corps did not, therefore, play a combat role but operated as a training and organisational resource for the entire Polish Armed Forces in the West. It was in Scotland and England that many schools and training centres for all kinds of military formations were located. And it was in London that the staff of the Commander-in-Chief was reconstructed and set up at the Rubens Hotel; the British capital was also where the resources responsible not only for the day-to-day operation of the armed forces but also for planning their development after the war were located.

Separate structures tasked with maintaining communications with, and providing support to, occupied Poland were also put in place. The programme of training elite special-operations paratroopers known as Cichociemni (“the Silen Unseen”) and their airlifting to Poland was the most spectacular of those operations. Many of those troops played an important role in the Home Army and in the anti-communist underground movement after the war.

FOR YOUR FREEDOM AND OURS

The Polish Armed Forces established in the United Kingdom had been preparing since 1940 to return to the mainland to fight alongside the Allies. However, due to the shortage of soldiers, only Brigadier General Stanislaw Maczek’s 1st Armoured Division had completed formation by the time the Allies landed in Normandy on 6 June 1944. By the end of July 1944, it had been transferred to France where it was attached to the First Canadian Army and took part in the final phase of the Normandy campaign. The 1st Armoured played a key role in the famous Battle of Falaise (19-21 August) and was instrumental in destroying the entire German 7th Army. Historians compare the task of the Polish division to that of a cork from a bottle in which the Allies trapped the enemy troops. After a victory paid for with heavy losses, the unit participated in the pursuit of enemy troops across northern France and Belgium, liberating Ypres and Ghent along the way. In the autumn, the division fought tough, victorious battles in the Netherlands over Breda and Moerdijk.

It is worth noting that the population of the liberated towns was particularly grateful to the Poles, who were doing their best to conduct military operations in such a way as to avoid destruction of houses and thus minimise civilian casualties. In the spring of 1945, after an operational hiatus of several months, the 1st Armoured took part in the offensive in western Germany, seizing the Kriegsmarine naval base in Wilhelmshaven and accepting the capitulation of its garrison on 6 May

On 18 April 1945, as they continued their progress across the Third Reich, General Maczek’s troops liberated the Oberlangen camp for women where participants in the Warsaw Uprising were, amongst others, imprisoned.

Many of the former inmates later joined the ranks of the Women’s Auxiliary Military Service, a formation established in 1944 as a spin-off of the Women’s Auxiliary Service. The Women’s Air Force Auxiliary Service and the Women’s Naval Auxiliary Service were also formed at that time.

Throughout the war, a total of around 7,000 female volunteers served in them, providing the fighting troops with vital paramedic services.

The 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, which had been formed with the mission to return to Poland by the shortest possible route, i.e. by air, also made its name during the liberation of western Europe. However, the airlifting of troops and their participation in Operation Tempest in occupied Poland proved unfeasible for technical and political reasons.

On 6 June 1955, the brigade was merged into the First Allied Airborne Army and deployed in Operation Market Garden. Polish paratroopers under the command of General Stanisław Sosabowski played a far greater role in the fighting over the Rhine River than originally planned. Given the unsuccessful attempts to capture the bridges at Arnhem and the trapping of the remnants of the British 1st Airborne Division by the Germans, the Polish landing proved to be godsent. Sosabowski’s troops were unable to reverse the fate of a poorly planned operation but their heroic sacrifice helped reduce the scale of the defeat. The high losses sustained in the Netherlands caused the brigade to lose its combat capability for several months. In May 1945, it returned to the mainland and, together with the 1st Armoured Division, became part of the Allied forces occupying Germany.

The Polish units were responsible for the administration of the Emsland district, providing shelter and assistance to compatriots returning from camps and forced labour. The 1st Armoured Division and the 1st Independent Parachute Brigade were demobilised and disbanded in 1947 together with the rest of the Polish Armed Forces fighting alongside the Allies.

A TRAIL OF HOPE

After the German attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Soviets, who had earlier seized the eastern borderlands of the Second Polish Republic, changed their hitherto hostile policy toward the Polish government and Poles. On 30 July 1941, General Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to London Ivan Mayski signed a treaty under which the two countries resumed the diplomatic relations severed in 1939, declared the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact null and void and concluded an alliance against Germany. It was also agreed that a Polish army would be formed on the territory of the USSR from among Polish citizens released from prisons and camps. On 14 August 1941, the agreement was expanded to include a military agreement which regulated in detail the army formation process.

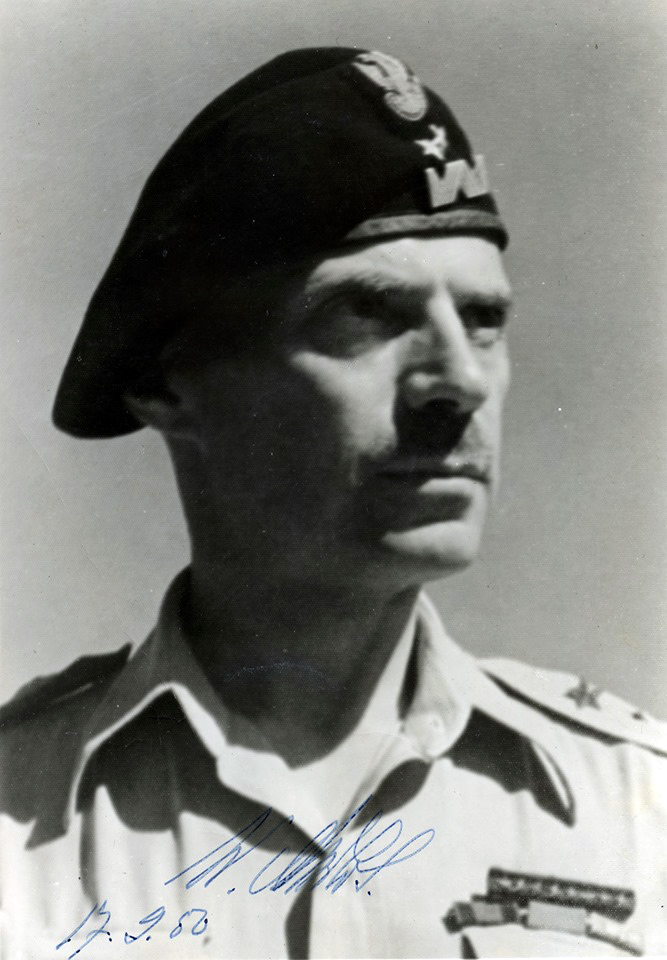

Command of the nascent army was entrusted to Brigadier General Władysław Anders, freshly released from a Soviet prison. Despite the difficulties piled up by the Soviet bureaucracy and a shortage of supplies and officers, he had managed to form a nucleus of the army by the summer of 1942. Six infantry divisions, a lancer regiment, a communications regiment and training centres were planned, but most of these units were operating at cadre strength, the 5th Infantry Division being the only one to reach combat readiness. General Anders’ opposition to the plans to throw that unit into battle even before the formation of the army’s entire force was completed gave Stalin an excuse to get rid of an inconvenient ally. By reducing food supplies, he forced the Polish authorities to accept the evacuation of troops to the Middle East, a move he had agreed on with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

A total of about 115,000 Polish citizens were transported in two stages across the Caspian Sea to British-administered territories. Thanks to the creation of cadet units and the Women’s Auxiliary Service, thousands of women and young men formed part of the evacuated army. About 35,000 civilians were also rescued at the time, including about 12,000 children. After crossing into Iraq, General Anders’ troops became the backbone of the Polish Army in the East. These forces helped the British maintain control of the Middle East.

On 21 July 1943, the Polish II Corps was formed from the Polish Army in the East. It included, amongst others, the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division formed in May 1942 from the Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade. The brigade was formed in 1940 in Syria, from where it was evacuated to Palestine after the fall of France. Its troops gained fame for their engagement in the months-long defence of Tobruk in 1941 and the battle of El-Gazala.

In addition to the Carpathian Division, the Polish II Corps commanded by General Władysław Anders comprised the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division, the 2nd Armoured Brigade. the 2nd Artillery Group, and later also the 1st Independent Commando Company. In the winter of 1943/1944, the corps was sent to the Italian front

Its combat trail started with the bloody fighting at Monte Cassino in May 1944. The capture of this hill, after several unsuccessful attempts by the Allies, earned the Polish Armed Forces fame and disproved claims of their inaction in the war. Then, pursuing the enemy, the corps captured Ancona, and ended its glorious combat trail on 21 April 1945 in Bologna, playing a decisive role in the liberation of the city.

The II Corps was the largest combined force of the Polish Armed Forces in the West to operate alongside the Western Allies. The massive influx of volunteers in the final phase of the war (recruited, amongst others, from among the prisoners of war, that is Poles forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht) enabled the development of units forming part of the corps. For example, the armoured brigade was upgraded to the 2nd Warsaw Armoured Division, and the commando company was redesignated as the 2nd Motorised Commando Battalion. As a result, by the end of 1945, the corps numbered more than 107,000 men. In the autumn of 1946, the Polish II Corps was transported to Great Britain where it was gradually demobilised and finally disbanded on 10 July1947 together with the entire Polish Armed Forces.

NOT ONLY ON LAND

The Polish troops in the West consisted of all types of armed forces, including air force and the navy. What’s more, airmen and seamen were among the first troops to arrive in the allied territories of France and Britain. As high-class specialists, pilots and mechanics started to be flown to the West as early as September 1939. The first seamen arrived in Britain as part of the planned evacuation of the Baltic Fleet to escape the inevitable annihilation by the more powerful Kriegsmarine.

By May 1940, the Polish Air Force in France had already numbered 6,863 men. During the June battles, the airmen scored some 50 air victories. Most of them (145 fighter pilots) later took part in the Battle of Britain, fighting as part of both the Polish 302nd and 303rd squadrons, as well as British squadrons. Destroying at least 131 enemy aircraft, the Poles made a major contribution to repelling the German air strike on the British Isles.

More Polish fighter and bomber squadrons entered combat later on, taking part in Allied air operations over France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy. Worthy of particular notice is the activity of the Polish Fighting Team established in 1943 under the command of legendary fighter ace Stanisław Skalski.

During the African campaign, Skalski’s pilots shot down and damaged more than 30 German aircraft. It is also worth mentioning that special-purpose transport aviation units performed hundreds of flights between 1941 and 1945 to drop supplies and paratroopers into Poland and other occupied countries.

During World War II, Polish airmen performed a total of about 85,000 combat flights, shot down 778 aircraft and probably destroyed a further 207. Their other successes included shooting down 190 V-1 missiles, dropping some 15,000 bombs and sea mines, destroying several thousand motor vehicles and sinking some 200 enemy ships. The vast majority of these achievements are to the credit of personnel operating in the West.

The Polish Navy engaged in battles with German naval forces from the first days of the war. During several years of struggle, Polish seamen earned distinction for their contribution to the Norwegian operation, the Battle of the Atlantic, convoy escorts and operations in the Mediterranean. Polish ships participated in 665 clashes and 20 naval battles, escorted 787 convoys and carried out 1,162 patrolling missions.

They sank 7 enemy surface ships, 2 submarines and 39 transport ships, as well as damaged a further 16 surface ships and 8 submarines. They shot down 20 enemy aircraft. Polish vessels (2 cruisers, 10 destroyers, 5 submarines, 12 chasers and torpedo boats) covered a total of about 1,213,000 nautical miles.

Sailors of the Polish Merchant Navy also made a significant contribution to the war effort. In September 1942, the Merchant Navy numbered 42 ships with a total tonnage of about 140,000 GRT. Polish ships were engaged in convoy operations in the Atlantic and in military transport operations, such as carrying Allied soldiers during the Normandy invasion and the landing on the Malay Peninsula. In the course of these operations, nearly 200 seamen were killed and 17 ships were sunk.

UNDER ANY COLOURS BUT WHITE...

The Polish Armed Forces in the West were formed thanks to the determination of officers and soldiers of the pre-war Polish Army who refused to accept defeat and the occupation of their homeland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. In a more or less organised manner, they made their way to France and Great Britain to continue their struggle for the liberation of Poland alongside other countries in the true tradition of fighting for “your freedom and ours”. The army personnel comprised not only Poles but also numerous representatives of the ethnic minorities living in the Second Polish Republic, such as Jews, Ukrainians, Belarusians and even Germans. Volunteers from across the world were not only members of the Polish diaspora but also people with no Polish roots; they simply shared the belief that the battle with the totalitarian aggressors had to be fought to final victory. An estimated 300,000 men joined the Polish Armed Forces in the West and some 15,000 lost their lives.

Unfortunately, the alliance with the Soviet Union turned out to matter more to the Western powers than their commitments towards their most loyal ally. As a result of their subservience to Joseph Stalin, Poland found itself in the Soviet sphere of influence, which meant a new period of enslavement. For this reason, most of the soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces in the West decided not to return home, choosing to make a living abroad. Those who returned faced repression from the communists.

The Regimental Colours of the Polish Armed Forces were deposited in the Polish Historical Institute in a sad ceremony that took place on 10 July 1947. Władysław Anders gave then a speech, the last part of which became a testament to the Polish Armed Forces in the West. The execution of that testament was to be possible only after the fall of the Polish People’s Republic:

These Regimental Colours are sacred to us soldiers as they have led us from victory to victory. We took an oath of allegiance on these colours, pledging to fight for Poland until our last breath, like every righteous Pole would do. Our Regimental Colours bear the inscription: “God, Honour, Fatherland” and the image of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Jasna Gora and of the Gate of Dawn. The names of battlefields are commemorated there, as well as the names of cities so dear to all Poles, such as Warsaw and Lviv, Poznan and Vilnius.

We fought with deep faith in God and His justice, we upheld the honour of the Polish soldier who knows perfectly well how to distinguish bravery from petty-mindedness and righteousness from treachery. We were fighting while keeping in mind the vision of Poland and remembering our entire nation which despite the harshest of conditions, despite the losses and cruel disappointments, has never lost faith in the cause of regaining true freedom and independence. We are the flesh and blood of this Nation, and we consider it the greatest honour to be its members.

I do not know when but I feel and believe deeply that our Regimental Colours deposited here today will return to Poland in full glory, for the new glorious service of our Immortal Fatherland.

about autor

historian and museologist, a graduate of the Historical Institute of Warsaw University, specialising in military history. He combines his work with his passion for history, and his research with the promotion of its results through publications, exhibitions, lectures and historical tourism.

Since 2010, he has been engaged in the creation of the Józef Piłsudski Museum in Sulejówek, where he currently works. The author, co-author, translator or editor of dozens of publications devoted mainly to the Polish military history in the 20th century. A book lover and collector. His interests focus on the history of Warsaw and the north-eastern borderlands of the former Polish Republic.

Przypisy

1 B. Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski. Marzyciel i strateg, Poznań 2014; A. Garlicki, Józef Piłsudski, 1867–1935, Warszawa 1990; K. Kawalec, op. cit.; R. Wapiński, Roman Dmowski, Lublin 1988.

2 M. M. Drozdowski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Warszawa 1981; H. Przybylski, Paderewski. Między muzyką a polityką, Katowice 1992; I. J. Paderewski, Pamiętniki, Kraków 1961.

3 A. Bujak, M. Rożek, Wojtyła. Wrocław 1997; ks. M. Maliński, Droga do Watykanu. Wydawnictwo Literackie 2005; G. Weigel, Świadek nadziei, Kraków 2000; P. Zuchniewicz, Narodziny pokolenia JP2. Warszawa 2007.

4 R. W. Reid, Marie Curie. London 1974; F. Giroud: Maria Skłodowska-Curie, Warszawa 1987; S. Quinn, Życie Marii Curie. Warszawa 1997; M. Skłodowska-Curie, Autobiografia i wspomnienia o Piotrze Curie. Warszawa 2004.

5 S. M. Jankowski, Karski. Raporty tajnego emisariusza, Poznań 2009; W. Piasecki, Jan Karski. Jedno życie, t. 1-2, Kraków 2015-2017; E. T. Wood, Karski. Opowieść o emisariuszu, Kraków 1996; A. Żbikowski, Karski, Warszawa 2011.

6 A. Cyra, Rotmistrz Pilecki. Ochotnik do Auschwitz, Warszawa 2014; Auschwitz. Nazistowski obóz śmierci, red. F. Piper i T. Świebocka, Oświęcim-Brzezinka 1993.

A project financed from the funds of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers the Republic of Poland within the framework of the 2022 Polonia and Polish People abroad competition