POLISH NATIONAL HEROES OF THE 20TH CENTURY: WHAT DO THEY TELL US ABOUT OURSELVES?

Przemysław Waingertner

University of Lodz

What historical figures of their compatriots (whose mortal life has already come to an end and therefore can be fairly and justly evaluated) do Poles consider of paramount importance in the recent history of the state and nation? Who among them is regarded by contemporaries as rightfully belonging to the gallery of national heroes of the past century, one marked by the act of regaining independence twice (in 1918 and 1989) and the effort of building a sovereign state twice, but also by two bloody world wars, a heroic defence against Russian invasion in 1920 and decades of Communist and Soviet enslavement? What does this selection tell us about ourselves? What character traits, qualities of spirit, talents and skills do we value in our ancestors? Even a cursory reading of the answers to surveys on Polish heroes of the 20th century – conducted every now and then by both popular and serious history periodicals, as well as by institutions of science and culture – gives us an idea who the winners of the ranking are. These are: Józef Piłsudski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Saint John Paul II, as well as Marie Curie-Skłodowska. Jan Karski and Witold Pilecki have been the recent additions to this list thanks to awareness raising efforts undertaken by different communities and institutions.

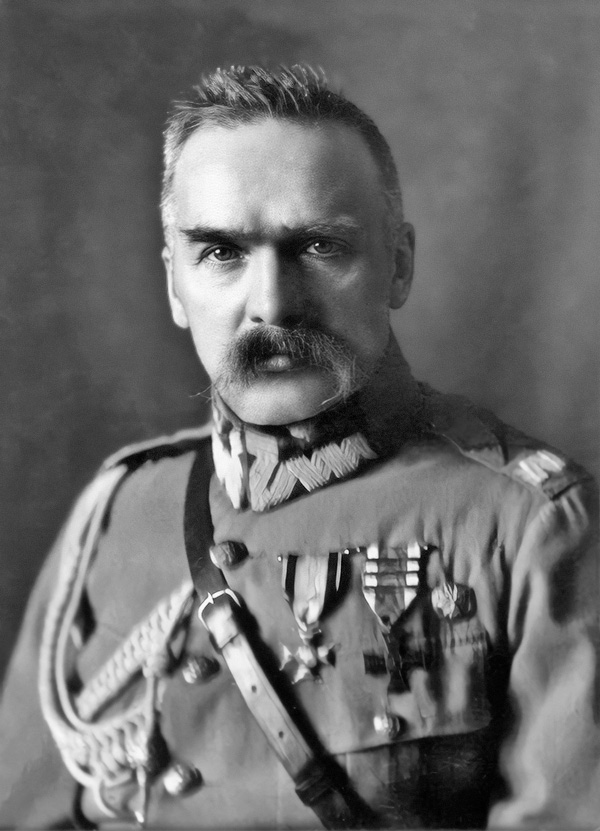

JÓZEF PIŁSUDSKI

So let us start with the leader of the list: Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935). A conspirator for independence at the time when Poland was partitioned. An exile to Siberia. A leader of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) championing the cause of a free and socially just Republic. An editor and publicist at Robotnik (The Worker), a mouthpiece of the socialist pro-independence agenda. An ardent advocate of transforming the revolutionary momentum of 1905 into another Polish national liberation uprising. One of the founders and commander-in-chief of Polish paramilitary rifle units in the Austrian sector of partitioned Poland. The commander-in-chief of the First Brigade of the Polish Legions fighting alongside Austria-Hungary against Russia during the Great War, and the head of the Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, POW) with its agenda of conspiring against all partitioning powers.

When Poland had regained independence, and as its political system and borders were being formed, he served as Chief of State, Commander-in-Chief, and later as First Marshal of Poland. Piłsudski advocated the idea of rebuilding Poland as a great federation together with Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus. While inspired by the history of the multinational and powerful Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, this ambitious project sought, at the same time, to promote the right of nations to self-determination

(considering their weaknesses, the nascent nations of Lithuanians, Ukrainians and Byelorussians were in practice faced with the prospect of division of their lands between Poland and the new Soviet, but still imperial, Russia as an alternative to federation and the chance of own statehood it offered).

Marshal Pilsudski also proved to be a formidable opponent of the Red Army in the great bloody battles of 1919-1920. An architect of the democratic system of interwar Poland, he was one of the authors of the country’s framework of civil and social rights and the driving force behind the swift establishment of the Legislative Sejm. At the same time, he was fiercely critical of the March Constitution (which, in his view, disastrously tilted the balance of power away from the president and the government in favour of the Sejm) and the unstable rule of parliamentary governments in the Second Republic in the first half of the 1920s. Last but not least, he carried out a coup d’état in 1926 (May Coup) and is credited as the actual father of Polish authoritarianism, ruling the country as a dictator 1

Pilsudski was a romantic realist – an apparent oxymoron! His romanticism manifested itself in the adoption of a maximalist strategic goal: a sovereign and secure Poland. His realism was, on the other hand, visible in his pragmatic, opportunistic even, tactics to enable the achievement of that goal. It was because of this paradoxical mix that, depending on the changing circumstances, the former socialist leader would rely on firing squads and champion the idea of the Legions when faced with the prospect of war, whereas the born dictator would order elections to the Legislative Sejm (so as to bind the citizens to the state while giving the Polish authorities democratic legitimacy and international recognition in the era of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919) only to later overthrow the “Sejmocracy” by force and establish authoritarian rule. Was the May coup intended as a prelude to a radical overhaul of the state? Why then did Piłsudski disregard plans for a new constitution, the problem of national minorities and the key social and economic issue of land reform?! Why did he focus solely on the army and diplomacy? It is my theory that he was one of the few Poles – a tragically lonely “father” of independence revered by his compatriots for the restoration of the Republic – to realise that in the interwar period, which he regarded as a short interlude between war cataclysms, anticipating another great armed conflict, there was simply no time to repair the state! That the priority was to organise a strong army and forge strategic alliances. And that the Poles’ celebrated independence could turn out to be a short-lived affair without a happy-end….

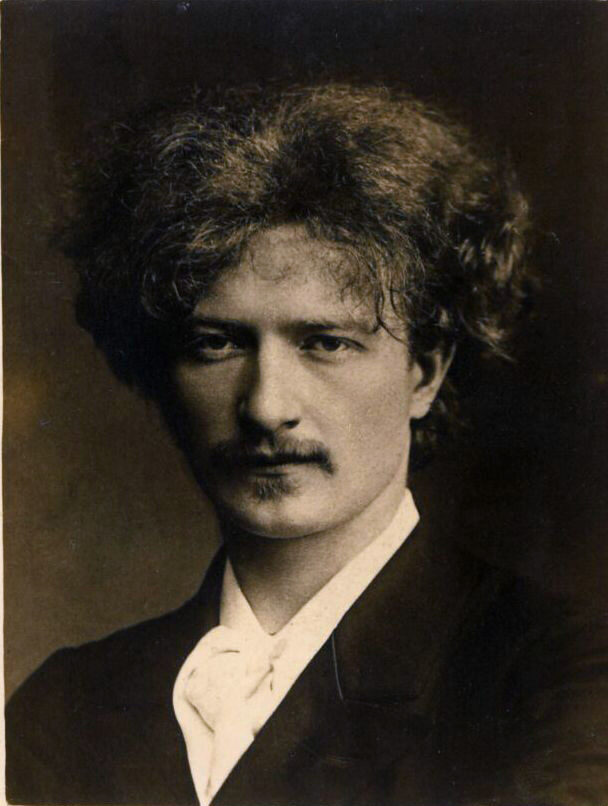

IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI

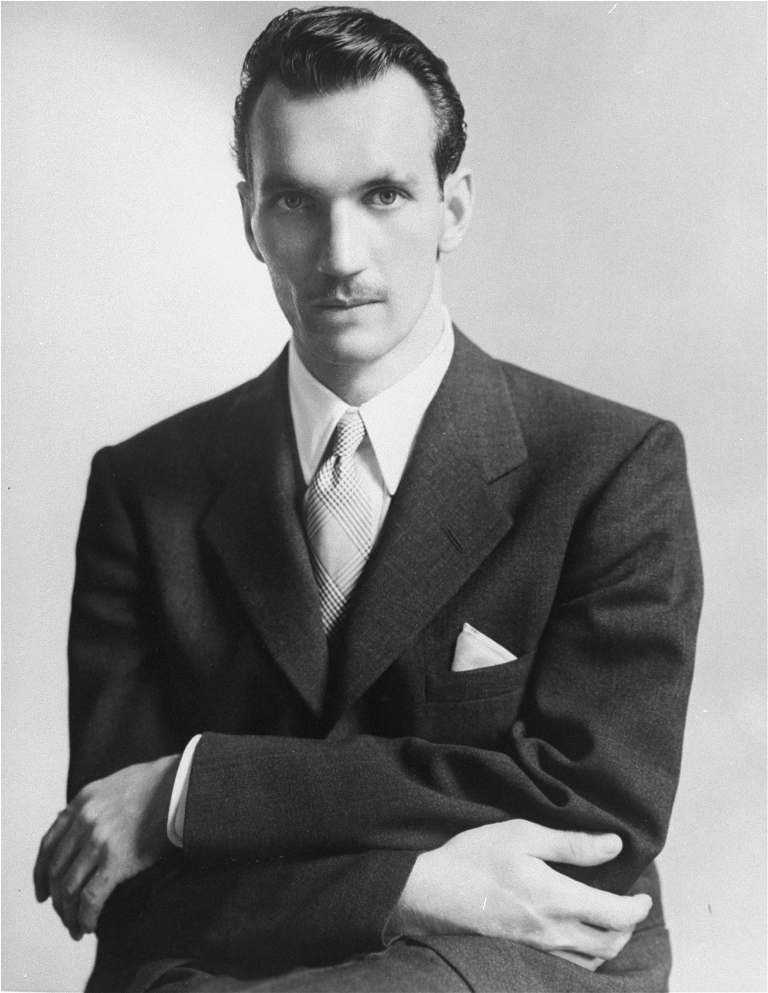

Another protagonist of this story is Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Born in 1860 to the family of Polish insurgents of 1830 and 1863, he was an extremely talented and hard-working pianist (often practicing continuously for 12 hours at a time), dubbed “the wizard of the keys”. He studied with the masters – Berlioz himself and Leschetizky – and performed countless concerts in Europe and the United States to audiences in the thousands, including Queen Victoria and President Woodrow Wilson. He was the only Pole whose opera was staged in New York’s legendary Metropolitan Opera, and friends with the great Polish actress Helena Modrzejewska. He fully deserved the title of the most famous Pole of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: while Piłsudski enjoyed recognition among politicians (or at least some of them), Paderewski was a household name among the political, social and cultural elites across the globe.

A piano virtuoso and great composer, he abandoned his lifelong passion for music to devote himself wholeheartedly to the cause of Poland’s restoration of independence. In 1910, he funded a monument in Kraków commemorating the Polish-Lithuanian victories at Grunwald. At the opening ceremony he delivered a patriotic speech that captured the hearts and minds of over 150,000 spectators who had arrived from all sectors of partitioned Poland to witness the monument’s unveiling.

During the years of World War I, he founded committees to help Poles in Paris, London and the Swiss city of Vevey. In the United States, he met with President Wilson and his advisor Edward House, lobbying tirelessly for Washington’s support for the cause of an independent Poland. As a result, the erection of an independent Polish state became one of Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points, the conditions for ending the war.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, he officially headed the Polish delegation as the Prime Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Polish Republic. During the Polish-Soviet War, he worked to establish the American Legion and the Polish-American Kosciuszko Air Squadron to support the troops of the Republic of Poland. He was a representative of Poland to the League of Nations. Even in his old age he remained committed to the Polish cause. When World War II broke out and Poland found itself under occupation, he headed the National Council of the Republic of Poland, an émigré parliament. He died in 1941 – to the end in the service of the Republic of Poland, respected as a great patriot and musician by both his compatriots and the entire Free World…2

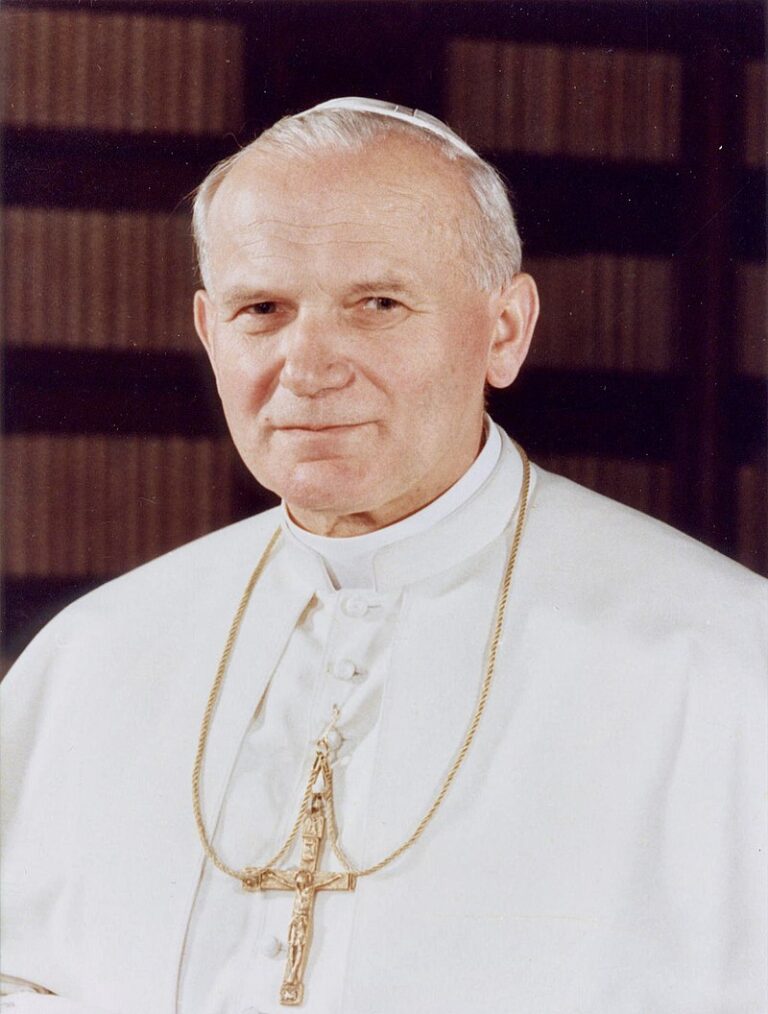

JAN PAWEŁ II

John Paul II (1920-2005) is another figure that is always mentioned by respondents, both Polish and foreign, when asked to name the most famous Poles. This is regardless of whether he is titled a saint, His Holiness, or “just” the Pope; whether he is lauded as the initiator and spiritus movens behind the great wave of world evangelisation and ecumenism, or criticised for his conservatism and aversion to the new Catholic aggiornamento; whether he is judged to be an inspired Catholic mystic or a subtle philosopher and intellectual of the Church; whether he is regarded as a spiritual shepherd of the persecuted and the poor, or a calculating player on the grand stage of world politics; and last but not least whether he is credited as the head of the Church, a spiritual guide and teacher, or as one of the most influential statesmen of the past century who contributed to the rise of the Solidarity mass movement in Poland and had a role in bringing about the bankruptcy of communism in Europe and in the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the end of the “Homeland of the World Proletariat”.

Before Karol Wojtyła was born to the world as pope and bishop of Rome in 1978, his life had been marked by drama. Born in the town of Wadowice near Kraków, a lover of poetry, playwriting and acting, he earned his living as a labourer under the German occupation during World War II.

When the war ended, he chose the path of a priestly vocation: from a seminary alumnus through cardinal to pope. The head of the Catholic Church and the leader of the masses of Catholics, he became famous as a pilgrim pope, preaching the Gospel on all continents, finding common ground with intellectuals, winning over the youth, and taking up the cause of the poor and repressed; the author and co-author of numerous encyclicals and apostolic letters, as well as the catechism of the Catholic Church; and an ally of the Western leaders hostile to communism and the Soviet Union in the 1980s: Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. For many – regardless of worldview or religion – he was and is simply a moral role model, one in such demand in today’s world3.

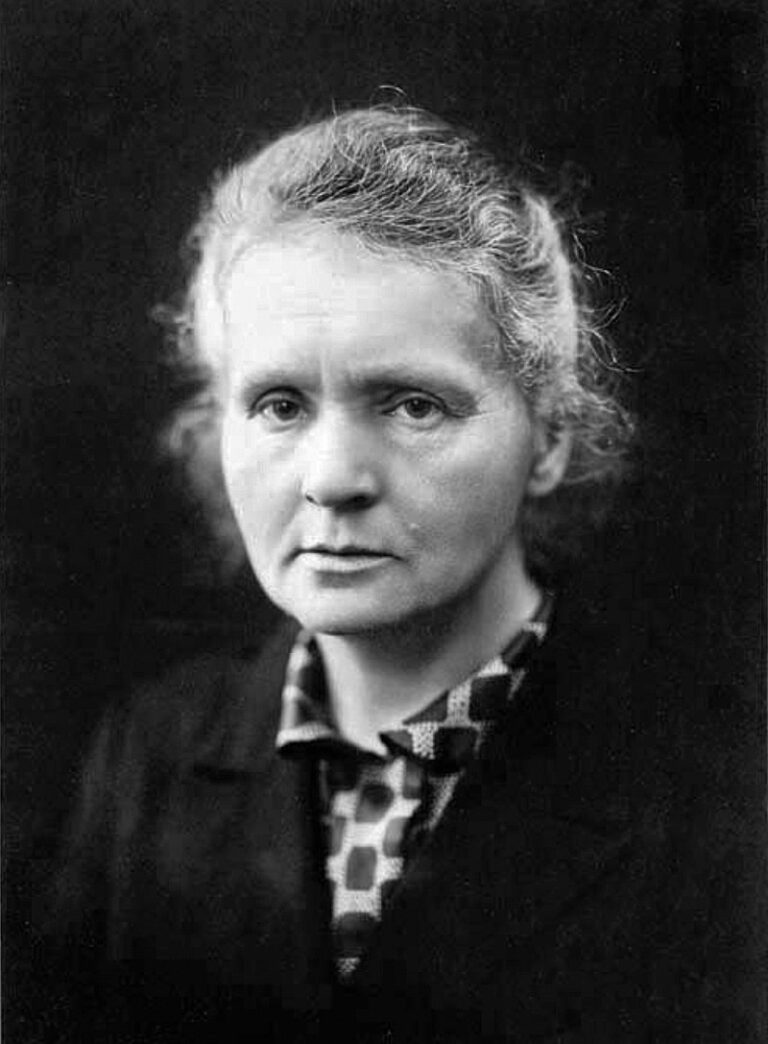

MARIA SKŁODOWSKA-CURIE

Another figure (and the only woman on this predominantly male list) is Marie Curie-Skłodowska – a true record-holder when it comes to a collection of “first” titles, although her other achievements are also spectacular. So let us start with the fact that she is the first Pole to be awarded the Nobel Prize (on two occasions, in 1903 and 1911, when Poland as a partitioned country was not yet on the maps of Europe).

he is also the first woman in history to receive the Nobel Prize; and the first person and only woman to date to win it twice. A discoverer of two new elements. The first woman to pass entrance exams in physics and chemistry at the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris, and the first female professor and head of the department (of physics) at this esteemed university.

Last but not least, the first and so far only woman to be buried in the French Pantheon – and the first person born outside France to be honoured in this way. A friend of the aforementioned great Polish composer and pianist Ignacy Paderewski. And finally – wife, mother, grandmother and mother-in-law of Nobel laureates. Like the beautiful Helen contested by Greeks and Trojans, Marie Curie-Skłodowska is the casus belli of a century-long war between the Poles and the French over whether she was Polish throughout (which she was!), or whether she became with time more of a French.

Born in 1867 in Warsaw, she left for France to study physics and chemistry at the legendary Sorbonne. A pioneer of a new branch of chemistry known as radiochemistry, she rose to prominence for her stellar achievements such as the development of the theory of radioactivity, techniques for separating radioactive isotopes and the aforementioned discovery of two new elements, radium and polonium. She is also credited with initiating research on treating cancer with radioactivity. At her inspiration, the French government allocated funds for the establishment of the Radium Institute as a centre of research in chemistry, physics and medicine. During World War I, she pioneered the use of radiology in field hospitals, saving lives of many soldiers. The world recognised her great achievements. As well as a double Nobel Prize winner, she was a triple laureate of the Academy of Sciences in Paris. Her scientific trophies ranged from honorary doctorates from the most prestigious universities, including Geneva, Manchester and Edinburgh, to memberships in Academies of Sciences in St. Petersburg, Bologna and Prague and the Kraków Academy of Learning in her native Poland. Her death in 1934 due to anaemia, but most of all radiation sickness which she had developed as a result of her research, was deeply mourned in Poland, France and by the entire scientific community across the globe4.

JAN KARSKI

Finally, let us have a look at two Polish heroes of World War II: Jan Karski and Witold Pilecki. Born in 1914 in Łódź, the former was a graduate of law and diplomacy from the University of Lviv, a first-in-the-class graduate of the school for mounted artillery officers in Włodzimierz Wołyński, and an employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A bright future awaited him: a successful career, foreign postings, prestigious appointments, most likely a happy marriage…

The war that broke out in 1939 put an abrupt end to all his plans and dreams, transforming a “child prodigy” and a star of Polish diplomacy into a man of bronze, a tough soldier and a tragic proponent of a lost cause. First there was the Polish September Campaign and Soviet captivity, then his escape and conspiracy under German occupation, Nazi torture after his arrest, an attempted suicide so as not to betray his fellow combatants, and finally his rescue from prison. Then he descended into the inhumane world of the Holocaust with his clandestine forays into the vestibule of hell, the Warsaw ghetto, and the hell itself, the Izbica camp. He authored a special report on the massacre of the Jews for the Polish government-in-exile and embarked on a courier mission to report Nazi atrocities to Polish authorities and the Allies with the hope of stirring them into action.

Karski repeatedly risked his life during the mission that started in late 1942, producing a report that was passed to the Polish government in London and further on to the Allies. Karski himself met with British and American military officers, politicians, influential social and economic activists, representatives of the media and the movie industry, as well as church dignitaries. He even conferred with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt himself. Never tiring in his efforts to spread awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust, he fervently pleaded with everyone who would listen to immediately do something to stop the Germans or at least slow down the grinding gears of extermination of the “chosen people”. Alas, his words fell on deaf ears. His harrowing accounts met with indifference, disbelief or a cynical explanation that the needs of the frontline took precedence over the task of saving civilians deep in occupied Europe. After the war, Jan Karski was recognised by Israel with honorary citizenship and the title of Righteous Among the Nations, enjoying a reputation of a political and scientific authority. Yet until his death in 2000 he lived in the shadow of the Holocaust, frustrated with a sense of failure to fulfil the most important mission of his life and one that proved impossible to achieve…5

WITOLD PILECKI

World and Polish fiction abounds in images of historical yet idealised great heroes, patriots, paragons of valour, chivalric and soldierly virtues – from Leonidas through Roland and Lancelot to Zawisza the Black. Meanwhile, the dramatic history of Poland in the past century produced a flesh-and-blood hero whose unparalleled courage, high morale, love for his homeland but also loyalty to universal values made him a role model of a soldier, a patriot and simply a human being. A cavalry captain (rotmistrz) born in 1901, Witold Pilecki – because this is who we are talking about – was the organiser and one of the leaders of the Polish underground scouting movement in the Russian Empire, as well as a participant in the struggle against the German army occupying the Polish lands. As a cavalryman, he fought in the Polish-Soviet War. In the Second Republic, he was not only a soldier, but also a social activist. After the outbreak of World War II, he fought in the Polish September campaign, later resorting to partisan warfare as a unit commander. Under Nazi occupation, he founded and became one of the leaders of the Secret Polish Army, later presiding over its incorporation into the Union of Armed Struggle (Związek Walki Zbrojnej), an armed organisation of the Polish Underground State. He was the author of the plan to have someone from the underground military infiltrate the Auschwitz concentration camp. That person’s mission was to organise a resistance movement and an intelligence network tasked to collect and transmit information about the operation of the “death factories”, as well to facilitate a mass escape or an attack by units of the Polish Underground on the camp to free the prisoners. He volunteered to carry out that mission himself, allowing himself to be captured and imprisoned in Auschwitz from 1940 to 1943.

After escaping from the camp, he participated in the Warsaw Uprising and was taken prisoner by the Germans after the city’s surrender. When the prisoner-of-war camp had been liberated, he joined the Polish Armed Forces in the West and returned to Poland after the war to organise an anti-Soviet conspiracy. Arrested, brutally tortured and sentenced to death by the Communists, he was murdered by them in prison in 1948.

Cavalry Captain Pilecki. A hero of three wars. A frontline soldier, insurgent and conspirator. A prisoner of concentration camps, German oflags and Communist dungeons. A hero of the fight against two totalitarianisms – for the sake of Polish independence, but also in defence of universal values: the dignity of the individual and an ordinary humanity.

The figures of national heroes are like mirrors, teaching Poles about themselves. We are looking for values, a national canon of commandments that we share or, realising our own shortcomings, that we at the very least aspire to observe. We regard those figures as role models and compasses – even if our own paths are sometimes crooked (or is it because of that?). Patriotism, sacrifice of personal interests pro publico bono, tolerance, empathy, courage of intent and act, respect for knowledge and diligence – this is the testament we read from the biographies of our great compatriots. This is how we want to see the Polish national character. This is what some of us are and what some of us aspire to be. Most importantly, this is what everyone can try to become….

about autor

Dr. Przemysław Waingertner: born in 1969, a historian (University of Łódź), a researcher of the history of the Second Polish Republic, Polish political thought and the history of Polish warfare in the 20th century, an author of more than a dozen books and more than a hundred research articles (“Dzieje Najnowsze”, “Przegląd Nauk Historycznych”, “Rocznik Łódzki”), a popularizer of history, a contributor to the History channel of the Polish Television (TVP Historia) and the “W Sieci Historii” monthly, the Vice-President of the Łódź branch of the Polish Historical Society, the Chairman of the Council of the Museum of Polish Children – Victims of Totalitarianism, a member of the Programme Council of the Janusz Kurtyka Foundation.

footnotes

1 B. Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski. Marzyciel i strateg, Poznań 2014; A. Garlicki, Józef Piłsudski, 1867–1935, Warszawa 1990; K. Kawalec, op. cit.; R. Wapiński, Roman Dmowski, Lublin 1988.

2 M. M. Drozdowski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Warszawa 1981; H. Przybylski, Paderewski. Między muzyką a polityką, Katowice 1992; I. J. Paderewski, Pamiętniki, Kraków 1961.

3 A. Bujak, M. Rożek, Wojtyła. Wrocław 1997; ks. M. Maliński, Droga do Watykanu. Wydawnictwo Literackie 2005; G. Weigel, Świadek nadziei, Kraków 2000; P. Zuchniewicz, Narodziny pokolenia JP2. Warszawa 2007.

4 R. W. Reid, Marie Curie. London 1974; F. Giroud: Maria Skłodowska-Curie, Warszawa 1987; S. Quinn, Życie Marii Curie. Warszawa 1997; M. Skłodowska-Curie, Autobiografia i wspomnienia o Piotrze Curie. Warszawa 2004.

5 S. M. Jankowski, Karski. Raporty tajnego emisariusza, Poznań 2009; W. Piasecki, Jan Karski. Jedno życie, t. 1-2, Kraków 2015-2017; E. T. Wood, Karski. Opowieść o emisariuszu, Kraków 1996; A. Żbikowski, Karski, Warszawa 2011.

6 A. Cyra, Rotmistrz Pilecki. Ochotnik do Auschwitz, Warszawa 2014; Auschwitz. Nazistowski obóz śmierci, red. F. Piper i T. Świebocka, Oświęcim-Brzezinka 1993.

A project financed from the funds of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers the Republic of Poland within the framework of the 2022 Polonia and Polish People abroad competition